It’s the luxuries that give it away. To fight corruption, follow the goods

In Summary

- Analysis for The Conversation by Dr Reza Tajaddini, Senior Lecturer in Finance, and Dr Hassan F. Gholipour, Senior Lecturer in Economics, Swinburne University of Technology

There is disquiet about the French owners of the luxury brands Luis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Givenchy and Gucci giving a whopping €300 million to the rebuilding of Notre Dame Cathedral. Such largesse, critics say, could be better used for humanitarian causes.

This is more than a rhetorical point. It is almost certain that some of the profits made by all sellers of luxury goods come from criminals who have siphoned off government funds. Rather than being spent on health, education and other social welfare programs, the money has been spent on luxury goods.

Luxury goods are used to facilitate corrupt transactions and launder dirty money. Using data for 32 high-income and emerging economies, we have found a strong correlation between luxury item expenditure and societal corruption.

Our findings confirm previous research, such as luxury car sales being substantially higher in OECD countries with higher perceived corruption levels.

We are not saying that luxury brands are doing anything criminal. Nonetheless they could make a great gift to the world by pitching in to build the institutional architecture needed to combat corruption.

Corrupt figures

Anecdotal evidence of the connection between corruption and luxury items is easy to find.

Right now, Malaysia’s former prime minister, Najib Razak, is on trial over the looting of billions of dollars from government accounts. Police raided his multiple homes and collected 280 boxes of luxury items estimated to be worth more than US$270 million. This included 12,000 pieces of jewellery worth up to US$220 million, 423 watches worth US$19.3 million and 567 handbags worth more than US$10 million.

Last year, Brazilian customs officials found luxury watches worth an estimated US$15 million in the bags of the entourage of Teodorin Obiang, vice-president of Equatorial Guinea. The son of Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, president since 1979, he was convicted of corruption by a French court in 2017.

Swiss authorities seized his fleet of luxury cars, including a Koenigsegg One:1 (one of just seven built, worth US$2 million) in 2016. The same year Dutch authorities seized his US$120 million super-yacht at the request of a Swiss court.

Super-yacht Ebony Shine has seven double cabins, a cinema, gymnasium, sauna, Turkish steam room, massage room, jacuzzi, swimming pool and helipad. Just the ticket for an unelected representative of an impoverished nation. yachtharbour.com

Super-yacht Ebony Shine has seven double cabins, a cinema, gymnasium, sauna, Turkish steam room, massage room, jacuzzi, swimming pool and helipad. Just the ticket for an unelected representative of an impoverished nation. yachtharbour.com

Equatorial Guinea, meanwhile, ranks 141 out of 189 nations on the UN’s Human Development Index.

The list goes on and on. When the Viktor Yanukovych was deposed as Ukrainian president in 2014, for example, his palatial home revealed wealth far in excess of his official income. So too did the home of his attorney-general, Viktor Pshonka, which included a nest of Fabergé eggs.

Calculating the correlation

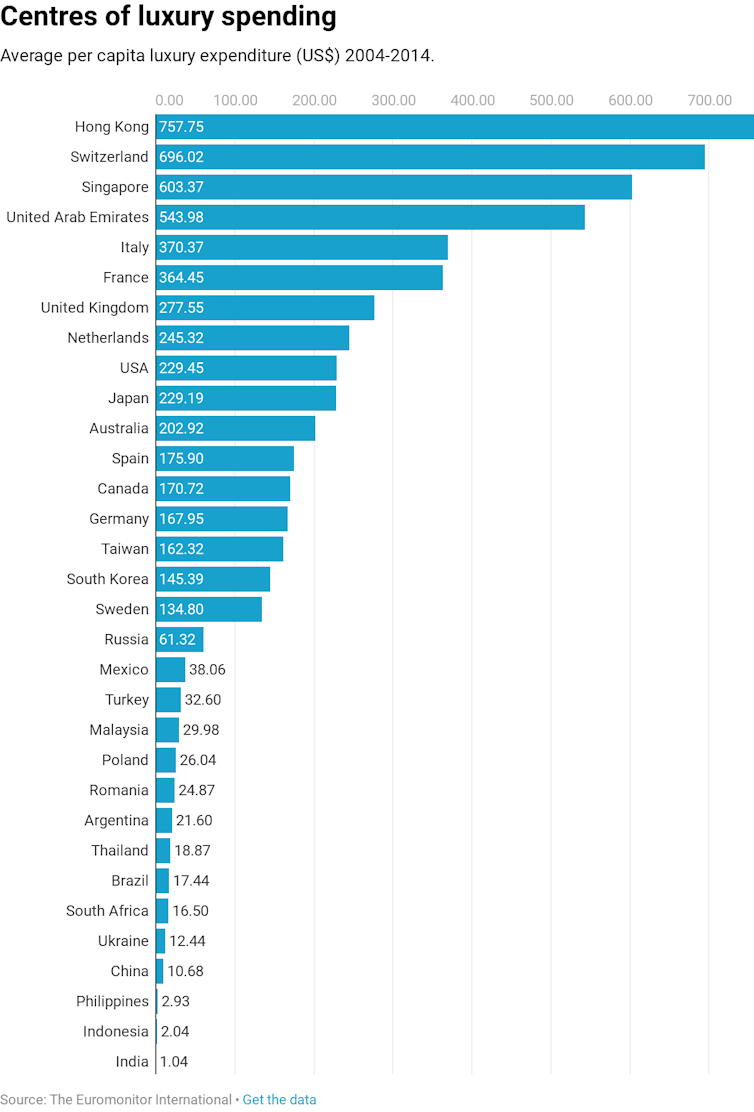

Our analysis covers all countries for which annual data on luxury spending per capita are obtainable, from 2004 to 2014. The sample includes the major emerging economies (Brazil, China, India, Russia and South Africa) and major high-income countries (US, Japan and Germany). Collectively the 32 sample countries represent about 85% of the world’s GDP.

We have cross-referenced these data with two corruption measures: the World Bank’s Control of Corruption Index, and Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.

Our calculations make allowances for variables such as relative wealth and spending by tourists. Greater spending on luxury goods is to be expected in richer nations and in international travel hubs such as Singapore, Hong Kong and Dubai. We have also controlled for factors such as inequality, with demand for luxury goods increasing as the income gap widens.

Our results suggest stronger anti-corruption controls reduce luxury spending. More press freedom and information transparency help too, presumably because this increases the chance of corruption being exposed.

Conspicous consumption

In countries where paying bribes to government officials to secure government contracts or operating licences is common practice, luxury goods are often used instead of direct monetary payments. Such “gifts” do not leave a transaction trail so are less likely to result in legal action against corrupt officials.

Another explanation for the link between corruption and luxury spending is that corrupt individuals send signals about their “services” by demonstrating a lavish lifestyle beyond their official source of income. It is a form of conspicuous consumption – buying something not for its intrinsic utility but as a signal to others.

Transparency International notes in its 2017 report Tainted Treasures: Money Laundering Risks in Luxury Markets: “For individuals engaged in corruption schemes, the luxury sector is significantly attractive as a vehicle to launder illicit funds. Luxury goods, super yachts and stately homes located at upmarket addresses can also bestow credibility on the corrupt, providing a sheen of legitimacy to people who benefit from stolen wealth.”

Cleaning up the luxury market

We agree with Transparency International that laws, policies and practices to combat this connection are underdeveloped.

Anti-corruption policies need to include monitoring luxury markets and developing regulations that increase transparency in luxury gifting.

The merits of doing so are demonstrated by anti-corruption efforts in China. In 2012 the Chinese government initiated plans to track corruption by looking at luxury goods ownership. As a result, consumption of luxury goods fell from US$93.48 billion in 2011 to US$73.1 billion in 2014.

There needs to be established global policies. The countries that host the largest luxury markets – China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the US and Britain – must also do more to ensure sellers of luxury goods follow due diligence and reporting requirements.

In Britain, for example, Transparency International reports that auction houses (such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s) filed just 15 of the total 381,882 suspicious transaction reports made to law enforcement authorities in one year.

In Antwerp, the largest diamond exchange in the world, suspicious transaction reports by precious stones dealers were totally lacking.

Luxury goods dealers have too little motivation to ensure those buying their trinkets and toys are not using money gained corruptly.

If the contribution of France’s luxury empires to rebuild one of Christendom’s most famous churches sparks a conversation about the problems of the luxury goods market and what can be done to to fight corruption, that will be a positive.

More than one French icon is on the line.![]()

Written by Dr Reza Tajaddini, Senior Lecturer in Finance, Swinburne University of Technology and Dr Hassan F. Gholipour, Senior Lecturer in Economics, Swinburne University of Technology. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.