How a ‘repair economy’ creates a kinder, more caring community

In Summary

- Analysis for The Conversation by Katherine Wilson, Author and educator, Swinburne University of Technology

John switches on the power saw he’s bought secondhand on eBay. The machine “arcs” – shooting out a visible electric charge. So he takes it apart to investigate. He identifies the problem: the field coil, a current-carrying component that generates an electric field. Once fixed, the saw works as new.

I met John during my doctoral research into tinkerers — people who love to adapt and repair things. But many things have become harder to fix.

Just a few decades ago, manufacturers packaged everyday appliances with instructions on how to repair them. Now they come with danger warnings and threats that doing so will void the warranty.

Read more: To beat the 'throwaway' waste crisis, we must design loveable objects – that last

Repair is discouraged by unavailable replacement parts, glued assemblies and tamper-proof cases that are difficult to open. So we discard things rather than fix them.

Much research suggests this harms more than the natural environment. It also affects our mental environment. There’s a connection between the way society treats material objects and the way it treats people.

Returning to an economy of repair could help create a kinder, more inclusive society. By mending broken things we might also help mend what’s broken in ourselves.

Repair is an investment of ourselves

The environmental case for a repair economy is obvious. It saves natural resources and reduces waste.

The product of our discard economy: a woman scavenges for recyclable plastics at the Dandora dump near Nairobi, Kenya. Daniel Irungu/EPA

There’s also a strong economic case. In his book Curing Affluenza, Australian economist Richard Denniss argues a community that repairs its goods “would employ more people, per dollar spent, than a community that instinctively disposes of them”. It would create more high-skill jobs and reduce the cost of living.

The social case is as strong. As Europe starts banning the disposal of unsold and returned consumer products, a mounting body of research shows that repair economies can make people happier and more humane.

During research for my 2017 book Tinkering: Australians Reinvent DIY Culture, I learned how material repair generates a deep sense of care, pride, belonging and civic participation.

Even solitary acts of repair involve a community of influences. Through acts of repair we experience products as expressions of our collective knowledge. Repaired products become bearers and extensions of personhood: like genomes, they carry their pasts within their presence.

By contrast, product obsolescence “blocks our access to the past”, argues Francisco Martínez, an ethnographer at the University of Helsinki. His research found repair was “helping people overcome the negative logic that accompanies the abandonment of things and people”. Repair made “late modern societies more balanced, kind and stronger”. It was a form of care, of “healing wounds”, binding generations of humanity together.

Like Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, Martínez draws parallels between the displacement and neglect of objects and those of people.

In Estonia, Martinez says, repairing things “establishes continuity, endurance and material sensitivity” in a society disrupted by Soviet-style socialism and subsequent transition to capitalism:

Contemporary mending and the reluctance to dispose of material possessions can also be a way to resist dispossession and adapt to convoluted changes; the act throwing away is perceived as a threat to memory, to security, and to historical and ecological preservation.

Similar observations have been made in different economies.

Studying Londoners living in reviled council flats following the Thatcher years, British anthropologist Daniel Miller observed residents who fixed their kitchens. Those with strong and fulfilling social relationships were more likely to do so; those with few and shallow relationships less likely.

Miller is among many scholars who have observed that relationships between people and material things tend to be reciprocal. When we restore material things, they serve to restore us.

Right to repair movement

Repair economies don’t regard material things as expendable. They relocate value in the workings, relations and meanings of things. By contrast, consumer economies encourage us to relate with products in ways that damage the planet and promote a kind of learned helplessness.

In response, the global “right to repair” movement has mobilised.

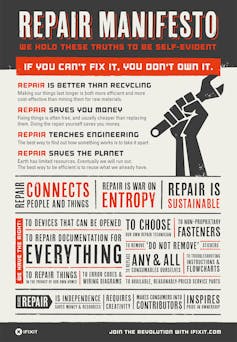

The Repair Manifesto. www.ifixit.com

Initiatives include community tool libraries and repair cafés, where people take their broken things, share tools and get expert guidance on how to fix them. There are swap-meets, Remakeries, Mens’ Sheds, visible mending workshops, Hackerspaces, Restart Parties and Commons Transitions enterprises.

Such “glocal” — at once global and local — initiatives reinscribe humane values into mass culture. They encourage participatory citizenship and create informal exchanges of knowledge, skills, materials, goodwill and values. They create what sociologists call cultural capital, the benefits of which are recognised in public health funding of initiatives such as Men’s Sheds.

In Europe, environment ministers are pushing laws obliging manufacturers to make appliances repairable and enduring. Many US states are considering “fair repair” laws, and federal authorities have deemed it unlawful for phone and other tech manufacturers to prevent owners repairing their products. In Australia, state governments are considering ways to promote a “circular economy”, in which material resources circulate for as long as possible.

Read more: Explainer: what is the circular economy?

We already have the tools to move away from an economy that values overconsumption and wasting resources. Doing so would allow us to fix more than just our products.![]()

By Katherine Wilson, Author and educator, Swinburne University of Technology. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.