Apple Arcade and Google Stadia aim to offer frictionless game streaming, if your NBN plan can handle it

In Summary

- Analysis for The Conversation by Dr Steven Conway, Swinburne University of Technology

Two of the biggest tech companies in the world, Apple and Google, are launching cloud-based gaming services this year.

Apple Arcade, due for release in two days, will ultimately go head-to-head with Google’s Stadia when the latter launches in November. And both will also be battling a surprising foe: friction.

In this context, “friction” means anything that increases inconvenience for the user. Friction makes you take extra steps, think more than necessary, or work harder to get the service you want. In designing a gaming platform, friction is bad.

Both companies will attempt to reduce friction by using cloud technology to store digital resources and services on their own servers, and deliver them to clients through the internet.

The game files will thus be stored and shared in much the same way that documents or photos are currently handled via DropBox, Google Drive, and Apple’s iCloud.

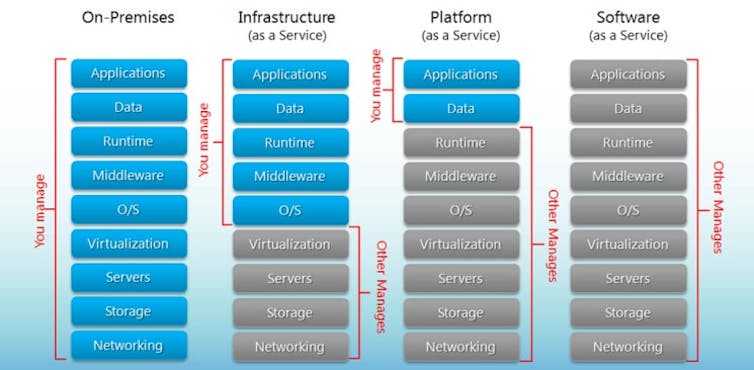

Specifically, Apple Arcade will use a model called “infrastructure as a service”. As long as you have an Apple device, you can play hundreds of games at any time, from any location, including offline (once you’ve downloaded the game).

This model outsources the problem of data storage to remote data centres around the world. The user’s device remains responsible for the operating system, maintenance of the software (such as patches and graphics drivers) and real-time processing of data.

Google Stadia is planning to use a slightly different model, called “platform as a service”. This means Google will take care of all the maintenance and processing requirements too, so the user’s device acts only as a receptacle for hosting the application and user data.

Google’s Stadia has a ‘platform as a service’ model which requires the user to maintain only certain aspects of data and the application on their device. Laura Bernheim / Author provided

Google’s Stadia has a ‘platform as a service’ model which requires the user to maintain only certain aspects of data and the application on their device. Laura Bernheim / Author provided

Budget-friendly gaming?

Both services will use a flat rate, monthly subscription model to let users play a multitude of games that would otherwise cost hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars.

For Apple Arcade all games are included in this fee, but you need suitable Apple hardware.

Ambitiously, Google’s Stadia promises to eradicate the limitation of hardware cost. Google will handle the hardware requirements, software processing and maintenance.

Instead of needing an expensive PC with the latest hardware and software, or dedicated gaming console, Stadia users simply need an inexpensive computing device such as a phone, Chromecast, or smart TV. All of the heavier processing requirements will be handled by Google, and the games simply beamed to your device.

However, unlike Apple Arcade, Stadia requires payment for individual games (neither of the services will have in-app purchases requiring additional payment).

When it comes to mobility, both Stadia and Apple Arcade will offer gameplay across multiple devices, from any location with all progress saved.

Sounds great right? What could possibly be the downside of these services?

We should heed culture critic Neil Postman’s warning regarding technology:

New technology is a kind of Faustian bargain. It always gives us something, but it always takes away something important. That’s true of the alphabet, and the printing press, and telegraph, right up through the computer.

The Faustian bargain in this context involves privacy and data, connectivity, and user control.

Privacy and data

As with any network technology, as soon as you opt into Apple Arcade or Google Stadia, your data becomes part of their system.

In digital games, it’s possible to track all kinds of user behaviour as you play.

While this might not lead to the building of psychological profiles and user manipulation on the scale of the Facebook Cambridge Analytica scandal, Google and other Silicon Valley giants have an awful record of respecting user privacy.

Network connectivity

Bad internet connection? Sorry, you’re out.

If you opt for Apple Arcade, this is less of a problem as you can download the game and play offline, but depending on your connection it can take minutes or hours before you can start playing - and let’s hope you don’t have a monthly data limit.

Meanwhile, to achieve 4K resolution streaming using Stadia, you require a steady flow of 20 megabits per second (Mbps). This will require a National Broadband Network (NBN) connection, but the entry-level NBN plan achieves a meagre 7Mpbs average.

Even for 720p resolution, which barely qualifies as high-definition, you need 10Mbps. Simply put, you’re going to need to pay for an upper-tier NBN plan, assuming that’s even possible in your area.

Mods and extras

Apple Arcade and Google Stadia also remove the potential for mods in gaming.

Mods (an abbreviation of “user modification”) are extensions that offer new levels, items, quests, or characters. These are made by amateur game developers and made available, generally for free, across the internet on various platforms such as Valve’s Steam.

The mod scene has had an enormous influence on gaming culture. The World of Warcraft 3 mod, Defense of the Ancients (DotA), popularised the now enormously successful Multiplayer Online Battle Arena (MOBA) genre. Counter-Strike began as a mod for Half-Life.

Both Apple Arcade and Google’s Stadia operate as closed systems, not allowing user modification in any substantial way. Any mod scene for these services is, at the moment, impossible by design.

And although Google is an enormous company, if the Stadia service is cancelled, all of its users will lose their individual game purchases.

A frictionless bargain?

We all want less friction in our lives.

We want things to be easy and accessible. In this sense, cloud technology offers a seductive bargain, encapsulated in one of Apple’s slogans: “it just works”.

Yet, in pursuit of things “just working”, we make sacrifices. We offer up our privacy, data and control.

The question becomes, what are we willing to lose in striking this bargain? Because, as Neil Postman reminds us, we will always lose something.![]()

By Dr Steven Conway, Senior Lecturer in Games and Interactivity, Swinburne University of Technology. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.