This laundry is changing the vicious cycle of unemployment and mental illness

In Summary

- Analysis for The Conversation by Aurora Elmes, Swinburne University of Technology

Margaret was depressed, jobless, broke and behind on her rent when the single mother of two heard about Vanguard Laundry Services, in Toowoomba, Queensland.

“I was desperate for work, any work,” she recalls. She started working at the laundry the day before she was due to be evicted.

Given her situation, Margaret was lucky to hear about Vanguard. The laundry is a social enterprise established specifically to provide jobs to people with mental illness. The factors Margaret felt had been barriers to jobs at other businesses – such as her age, gender and health – were no impediment to her employment.

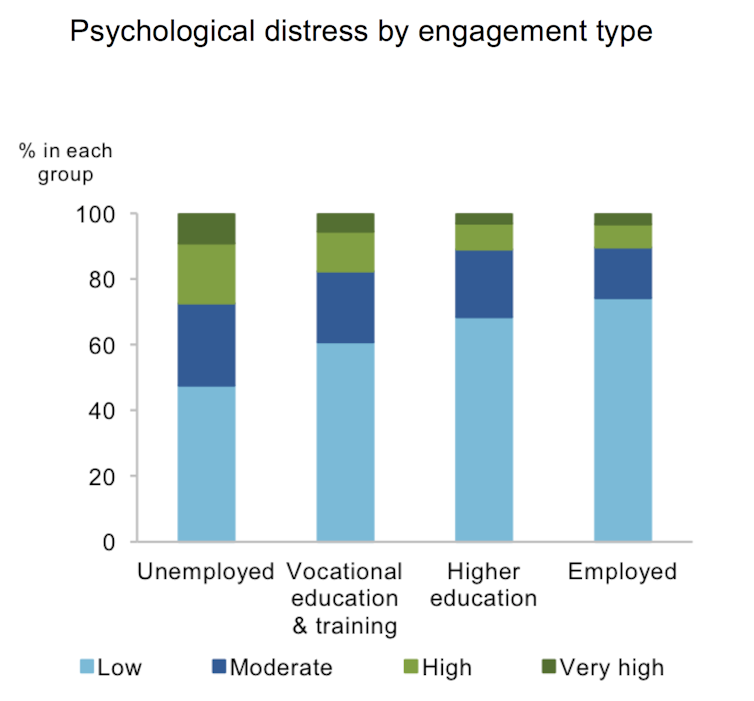

Employers generally tend to be far less accepting and understanding. According to Australian Bureau of Statistics data, 34% of unemployed women and 26% of unemployed men are dealing with mental illness. It makes it harder for them to get and hold down a job. Being unemployed also tends to harm mental health, so it’s a Catch-22.

The Productivity Commission’s draft report into mental health – which puts the economic cost of mental illness at A$180 billion a year – notes “particularly strong links between employment and mental health” and the importance of increasing job opportunities.

My research with Vanguard Laundry Services and the people who work there shows just how transformative a job opportunity can be.

Since it launched in December 2016, the business has provided jobs to about 78 people with histories of mental illness and long-term unemployment. My research has followed 48 of them. Most report significantly improved mental and physical health since starting work there. There have been concrete social benefits in terms of reduced reliance on public welfare and health services.

Flaws in the system

Under the existing federal Disability Employment Services (DES) system, which pays job service providers to assist people with disabilities, less than a third of those with mental-health-related disability actually obtain a job.

According to a Senate Committee inquiry, the employment service system creates “perverse financial incentives to churn unemployed workers into easier and more reliable income-producing outcomes, such as employability training, Work for the Dole, and job search programs”.

Financial incentives for employers are hardly better. The government will pay a wage subsidy up to $6,500 over six months for hiring someone registered with a job service provider for more than 12 months. These subsidies are open to any employer – including social enterprises like Vanguard Laundry – but this system can also be abused by profit-driven employers to offer only short-term jobs.

The Productivity Commission’s draft report makes several recommendations to improve employment outcomes. One is to put more resources into Individual Placement and Support (IPS) services, which include job coaching, assistance dealing with government services, education and on-the-job support.

There is evidence IPS is more successful than other employment interventions but, like other intermediary employment service approaches, there’s still the challenge of finding employers who are both willing to give someone a go and have a supportive work culture.

Many participants in my research spoke about past employment experiences that included unrealistically high workloads, verbally abusive supervisors and discrimination. Though employment is generally beneficial for mental health, a job with bad working conditions can be worse than unemployment.

Creating inclusive employment

This is where social enterprises like Vanguard Laundry Services have a role to play.

A social enterprise is a business whose core aim is to create public or community benefit. Like many of the 20,000 social enterprises in Australia, Vanguard’s core social purpose is to create meaningful employment opportunities for people experiencing disadvantage.

When creating employment is the reason an enterprise exists, working conditions can be more focused on the needs of workers. My research found staff appreciated having flexibility over their hours and tasks, having understanding and supportive supervisors, and being able be open about their mental health issues yet still be accepted.

From its launch to the end of June 2018, Vanguard’s social impacts have included:

- saving A$153,451 in welfare payments by raising the median income of target staff by $152 a week and reducing average Centrelink payments by A$102.25 a week

- saving A$231,767 in health costs, through employees spending a total of 138 fewer days in hospital.

These results highlight the potential benefits for society that the right mix of government policies can offer through supporting social enterprises.

By responding to some of the challenges within the existing employment system, social enterprises like Vanguard Laundry have the potential to both increase access to work for people with mental illness, and ensure the workplaces people move into are conducive to good mental health.

As Margaret’s story illustrates, access to decent work can make a drastic difference to a person experiencing mental illness and struggling to get by. “It’s just totally changed my life,” she says. “To be quite honest, it saved my life.”

Margaret’s name and some details have been changed to protect her privacy.![]()

By Aurora Elmes, PhD Candidate, Swinburne University of Technology. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.